Education systems all over the world have faced challenges during the pandemic in ensuring that children receive some educational continuity while schools are closed. I wondered how teachers and children across the four main areas of Seva Mandir’s educational provision were faring during lockdown.

As well as taking education to rural children during this period, one of the main focuses of the education team has been to ensure that children are not permanently lost to education as a result of the disruption caused by the pandemic.

Shiksha Kendras or bridge schools

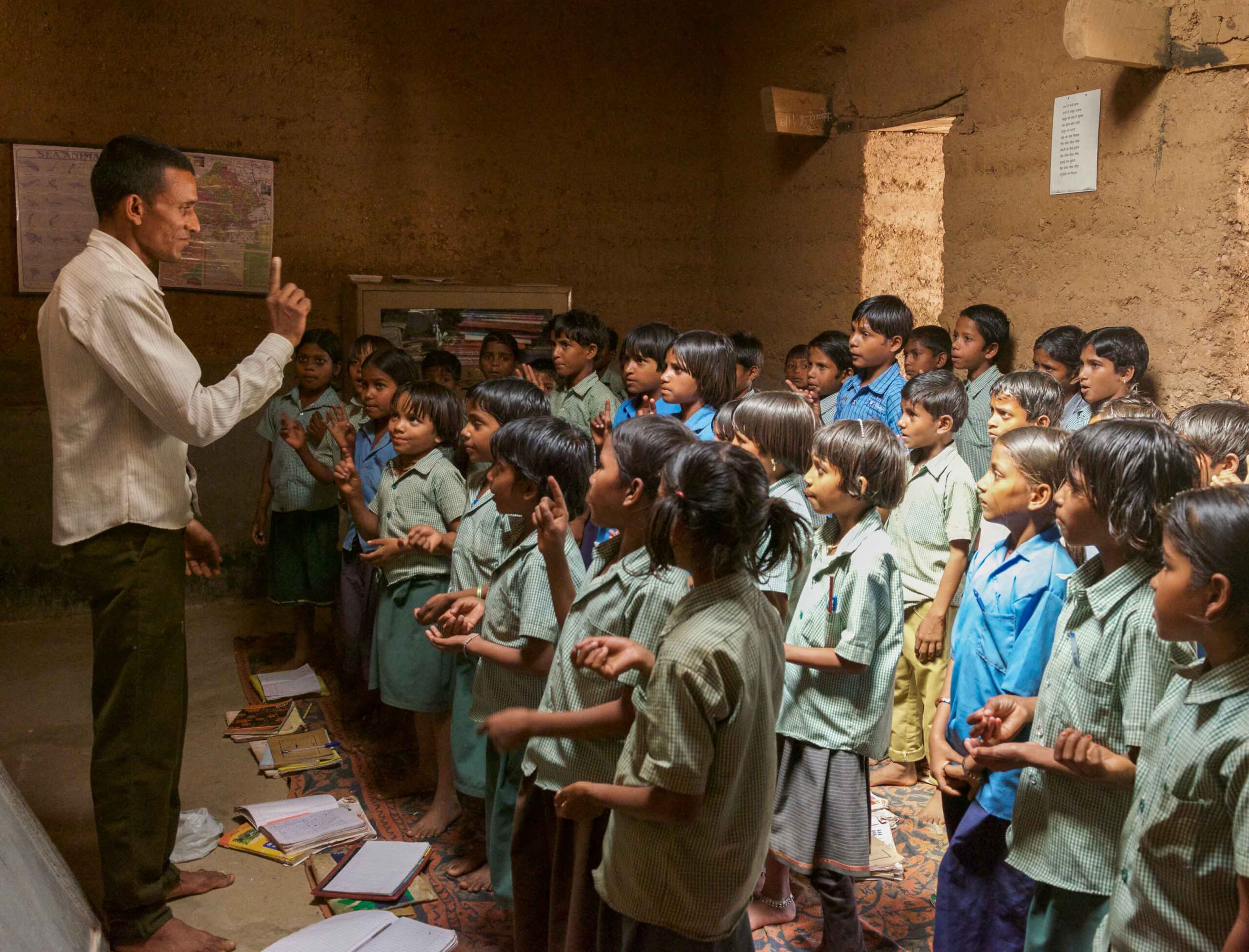

The Shiksha Kendras, or bridge schools, run by Seva Mandir in many rural villages throughout southern Rajasthan, do a wonderful job of providing education for children aged 6-14 who don’t have easy access to a functioning government or other type of school. The teachers recruited by Seva Mandir are drawn from the villages in which they work and, though most have had a very modest education themselves, Seva Mandir has trained them to run these little schools, encouraging children to learn – and, very importantly, persuading parents, who themselves may be uneducated, of the value of educating their children, girls just as much as boys.

To put this in context, in an area where the average per-capita income is 50 Rupees (about 50 p) a day, children make an important contribution to the survival of their family. Very young children look after goats, older children work in the family’s fields, girls fetch water, clean, cook and look after younger siblings. Many children from southern Rajasthan are also sent as migrant labour to neighbouring areas, to pick cotton, for example. The pandemic caused increased economic uncertainty. In many rural families, the main breadwinner lives much of the year away from the village in order to earn a little more in factories, mines or labouring jobs. These people lost their jobs and associated accommodation at the start of the crisis and were forced to travel home, resulting in reduced family income and at the same time an extra mouth to feed. It is little surprise, therefore, that children have come under increasing pressure to work, and that it has been harder for them to find a few hours a week for lessons. In households where children’s work was optional before, the lockdown has made their labour a crucial part of their family’s survival strategy.

It is vital to try to prevent children dropping out of education altogether, as experience shows that, once a child drops out, it is extremely hard to bring him or her back into schooling, and life chances are closely linked to years of schooling.

During this period, the Shiksha Kendra instructors have had more than just teaching to do. Their role has included ensuring that government teams and Seva Mandir’s aid programmes are aware of families in particular need of help (in the form of food, agricultural supplies, kits to help them observe the hygiene which is more crucial than ever). They have also acted as mentors for parents and children, providing advice on general wellbeing, as well as educational materials, and reminding parents of the importance of their children continuing to receive an education. Helping to keep a family afloat helps to ensure that children will have the opportunity to continue their education.

A very important part of their job has been to cover hygiene (handwashing, social distancing, mask-wearing), and not just for the children, but for parents as well. (It is often the children who learn the importance of hygiene at school and then pass this on to their parents and siblings.)

Parents have welcomed the chance to meet teachers more, and to see and understand what happens in a Shiksha Kendra as it is taking place so close to home rather than in a school to which children walk each day, sometimes covering several kilometres on foot.

The teachers have found that travelling to meet families in their villages has allowed them to bring back into schooling children who had not attended the Shiksha Kendra for some time. It has made it much easier to persuade parents to let their children resume learning, and teachers have been able to reassure parents that taking part in outdoor lessons in safe conditions would not increase children’s chances of catching the virus. It has taken time: at first teachers were finding that children were tired after their work for the family, but they helped organise children’s daily timetable to make provision for learning activities.

All in all, it is so encouraging to find that, rather than putting yet another barrier in the way of the education of poor, rural children from families where the level of education is often almost non-existent, the pandemic has actually resulted in better contact between teachers and parents, and parents’ increased understanding of the importance of children’s education. But everyone is now looking forward to the village schools being able to reopen soon.

Residential Learning Camp

For rural children who have dropped out or never been to school, Seva Mandir runs the remarkable Residential Learning Camp at its facility outside Udaipur. This centre runs three camps a year, each lasting 60 days, and children aged 6-14 are given board, lodging and clothes, and taught the basics (maths, Hindi, hygiene, some English, computer skills, sport) in groups of 10 children to one teacher (a ratio unheard of in Indian schools). The staff are chosen from the rural areas their pupils come from (important for communication in the local dialect, for one thing) and for their sympathetic attitude to these children, many from extremely poor, often one-parent tribal families. Children are expected to attend three camps within a year, timed to avoid the busiest farming periods. After 180 days of intensive education in the residential camps, the aim is that most will move on to full-time schooling, having gained the skills, confidence and enthusiasm to be able to cope in government schools.

The camp is one of the most remarkable places I have ever been, and I have never failed to be struck by the sense of joy radiating from children who, for the first time in their lives, begin to see the light that a little learning brings. For once, they are allowed time to play and be children, and they love it. There is no arduous physical work to do, they are surrounded by other children to play with, and cared for by gentle and encouraging adults – and they are well fed. No wonder many of the children I have interviewed over the years wanted to stay forever!

But the camp too has been shut for nearly a year now, as a result of the pandemic. The Seva Mandir education team has devised a decentralised version of the camp in order to continue its efforts to educate out-of-school children in the villages. It identified 150 rural children (about the number of pupils who usually attend the residential camps) and has taken education to their doorstep for the first two camps of this academic year. The hope is that the third term will see the pupils returning to the residential centre outside Udaipur.

Scholarship children in secondary school

The third arm of Seva Mandir’s education provision is the scholarship programme. A number of children from rural villages and from the poorest areas of Udaipur city are chosen each year to attend a secondary school run by Seva Mandir’s sister NGO, Vidya Bhawan Senior Secondary School (founded, like Seva Mandir, by the visionary Mohan Singh Mehta). They generally have some catching up to do to reach the level of the other pupils in the school, and remedial classes, as well as holiday camps, are conducted. The children from distant villages board in the school’s hostels, whilst those whose homes are in Udaipur are usually day pupils. The school gives pupils a much broader education than they would be likely to get nearer to home, with opportunities in arts subjects and sport offering a welcome chance for pupils who might be weaker academically, because of their earlier schooling, to excel. (Several girls who didn’t know hockey existed before coming to the school have gone on to play at regional level.)

Vidya Bhawan too was closed in March last year, but reopened in September. During the closure, teachers and Seva Mandir staff visited children’s homes, gave out assignments and study material, checked on their wellbeing and tried to enable them to learn online using mobile phones.

Now that the school is open, classes are both offline and online, and pupils all remain on campus for their safety. Extra classes in small groups are being held to help pupils make up for lost time.

Collaboration with government schools

The fourth element of Seva Mandir’s education programme is the relatively recent project to strengthen government schools with targeted support to help improve the education they can give. Government schools suffer from teacher absenteeism, a lack of subject-appropriate teachers, a scarcity of learning materials, and poor infrastructure and hygiene facilities. Seva Mandir has been creating Resource Rooms with books and educational games, and building toilets and water tanks to provide clean drinking water. It has also provided a team of trained school assistants (Shiksha Sahayaks) whose role is to demonstrate methods and work directly in classrooms, creating a support system for government teachers and helping them to take ownership of the educational relationship process. The Sahayaks appointed by Seva Mandir continue to be trained and there is some training proposed for government teachers in technical aspects, Resource Room concepts etc, in order to improve the quality of learning they can provide.

So far, this programme operates in 21 schools in 10 villages in one of Seva Mandir’s areas of operation.

Government schools were closed from March last year and began opening incrementally from January this year. During the lockdown, Seva Mandir concentrated on online training for the Sahayaks. As the lockdown began to ease (and India has been out of lockdown for some months now), efforts were stepped up to engage with enrolled children who were unable to get to school, and many primary-aged out-of-school children who would have been at Seva Mandir’s Learning Camp (see above). Shiksha Sahayaks were allocated a number of children and helped them keep up with their education through weekly group lessons. As the teachers of Shiksha Kendras found, parents responded very positively to being contacted by Seva Mandir’s team of support teachers and this has encouraged some government teachers to follow their lead. Communication with the government teachers themselves continued throughout the period in order to maintain and develop the positive atmosphere of collaboration for the benefit of their pupils.

Regular contact with parents, children and teachers has helped keep children in the education net, and, even though it has been hard to help children improve academically, they have at least been provided with some level of education and have been stimulated to keep learning.

Preschool provision

Seva Mandir provides preschool education in day-care centres or Balwadis, which cater to children aged 1-5 and offer a safe and caring environment for children while their mothers work. The centres also provide nutritious food, checks on nutritional levels, and much else. In recent years, the NGO has also been working to help strengthen the government-run day-care centres known as Anganwadis, training the women who run them, improving infrastructure and the nutrition provided, helping improve attendance of staff and children, and monitoring the centres’ running. The Balwadis and the Anganwadi project come under Seva Mandir’s Early Childcare and Development team, rather than the Education team, but I was keen to know how these programmes had been affected by lockdown.

Balwadis have had to remain closed during the period, but the dedicated Sanchalikas who run them, drawn, like teachers, from the areas in which they work, have spent their mornings cooking meals and preparing food parcels which are collected by the families of the children they would normally be looking after. Later, these women go to meet children in smaller groups and engage them in preschool activities such as singing, and they take toys with them to allow the children to play. (Few of these poor rural children have toys at home.) They also take time to chat to mothers.

The Balwadi Sanchalikas have been able to reach all the children who were attending the centres pre-lockdown, and the distribution of food has allowed them to retain contact with mothers (or other care-givers) and the children, though they are having to walk significant distances throughout the day to achieve this.

It is feared that the lack of full day-care provision will have an impact on children’s preschool education, even though their nutritional health should not suffer too much as a result of the closure. But mothers are finding it much harder to keep children safe while they work, often having to take little ones with them to the fields – one of the reasons the Balwadis were set up by Seva Mandir. There will also be a financial challenge to Seva Mandir, with greater numbers of children needing to be fed (since those who should have moved on to school have not been able to do so, and new children have joined).

The Anganwadis (government-run day-care centres) were also shut during lockdown, but the women who run the centres have continued to distribute government rations, identify vulnerable children and families, and keep an eye on those who may need help. They have also been spreading awareness of Covid-19 in the community, and collecting and uploading to a government portal villagers’ personal data to help in the rollout of Covid vaccinations.

The performance of the various Anganwadis in Seva Mandir’s area has been variable, but in many cases Anganwadi workers have gone out of their way to help children and their mothers. They have also become vital frontline workers, identifying cases of the virus in villages, helping people to quarantine and referring those in need to hospitals.

The centres reopened in early December, but only 5 or 6 children are allowed to attend at any one time, so most children are not present. Government rations continue to be distributed from the Anganwadis, and the Anganwadi workers visit homes with information and education packs and keep a check on children’s nutrition levels.

Seva Mandir’s training of the Anganwadi workers has resumed at local level, with staff being taught how to engage children at home.

The community malnutrition camps run by Seva Mandir have continued to operate in all 1,355 Anganwadis that the NGO covers and so staff have been able to continue treating malnourished children. Seva Mandir staff are observing that the number of malnourished children has increased during this difficult period, making these regular camps in the villages all the more vital in an area where child malnutrition was already all too common, and often very serious.

Conclusion

Having visited several of Seva Mandir’s village schools, the Residential Learning Camp, the scholarship children and the teachers/facilitators who seek to strengthen the government schools in the area, as well as many Balwadis and Anganwadis, it comes as no surprise at all to learn of the dedicated efforts made by all the Seva Mandir-trained field workers and the head-office teams to ensure that children miss out as little as possible. If ever proof were needed, this testing period has shown how right Seva Mandir is to select and train field workers from the villages, people who know their neighbours, understand their lives, and can speak to them as neighbours about the importance to their children of education and nutrition. They are trusted to offer help and advice and respected by the communities in which they live and work.

As so many of the villages or hamlets in which the schools and day-care centres operate are spread over a large area of difficult, hilly terrain (cracked and baked dry for most of the year, often crossed by rivers which become impassable during monsoons), it is no easy task for the teachers and the women who run Balwadis and Anganwadis to reach all the children under their care.

But if it is not surprising, it is nevertheless heart-warming to learn that the pandemic has actually helped field workers such as teachers connect better with some of the parents whose children they teach. Perhaps there will be some positive outcomes of this period which has been so difficult for the people of southern Rajasthan, as it has for all of us.

If you would like to help enable Seva Mandir to continue its life-changing work in education and early childcare and development, you can donate here by standing order or in a one-off gift. All donations through the Friends of Seva Mandir are given in full to Seva Mandir.

Read in more detail about Seva Mandir’s work in education and early childcare and development.

Read how the Covid-19 crisis affected the people in Seva Mandir’s work area, and some of the individuals who have been working to help their communities.

Felicia Pheasant, with thanks to Anu Mishra, Yashashwi Dwivedi and Victoria Haorokcham for their invaluable help